One of the Faces of Complexity

Today I am planning to write on a topic that is addressed literally in every book on software engineering. Yet I believe that too many projects (including my own) need more attention to some of the most basic ways of fighting complexity. Complexity is, yeah, a complex phenomenon, discussed in numerous sources, including a highly influential Brooks’s No Silver Bullet essay. Recently I wrote about Black, which insists on code made up of short lines. Quite often the only viable method of shortening the lines of a certain fragment of code is to move it into a separate function or class, which means increasing their overall count. Eventually I am also going to write about keeping cyclomatic complexity at bay, which also means having more functions and classes. This growing lists of entities needs to be organized properly, and that’s the complexity we are going to talk about here.

I am aware that not all sources of complexity are of "organizing your entities" type. However, I think this type is incredibly pervasive: if your code grows, the number of files / classes / functions / whatever grows as well. If you have a lot of something, you’d better think how to keep this something in reasonable order. It all sounds trivial, as we all know that algorithms should be wrapped into functions, functions and data make up classes, and groups of classes and functions form modules. What’s missing in this picture, and why many multi-component systems are so hard to analyze?

The Case of Hierarchical Systems

The organization I mentioned above (functions / classes / modules) suggest a typical hierarchical structure of the system: the component A is a part of the component B, which is a part of the component C. I’d say that the majority of reasonably complex systems we people design are created according to this scheme. A coffee machine contains separate units, such as a water tank, a coffee grinder, and a brewing unit. They, in turn, contain other elements: a water tank contains a filter; a grinder is made of an electric motor, steel blades and many other tiny parts; a brewing unit is a separate complex mechanism on its own. This approach can be considered as a variation of a (broadly understood) "divide and conquer" principle, here aimed to fight complexity. Much can be said about factors at work in this case, but everything mostly boils down to the possibility to treat individual units of the whole system as semi-independent structures. It opens many attractive opportunities: we can design and repair these units independently; we can reuse units elsewhere (say, the same coffee grinder unit can be found in different coffee machines); we can revise an internal structure of the unit if it doesn’t affect its external "interface". Very importantly, it also reduces the number of entities we have to deal with at one time. I can work with the system made of 5 or 10 components, while a structure of, say, 200+ interconnected elements is nearly incomprehensible.

I think the latter factor is the primary driver of hierarchical design: we can’t make something if we don’t understand it. Having said that, I have to add that the imposition of any specific type of design also restricts our options, and thus may lead to suboptimal solutions. Not everything we see around is hierarchical. Say, a human neocortex is a network-like structure of numerous interconnected elements, and it works reasonably well (but understanding how it works is a grand challenge). The limitations of hierarchical decomposition are known to anyone who tried, for example, to structure one’s own photo archive. One can start with a simple folder organization like this: let’s make a folder for each relevant Year/Month, then have a separate subfolder for each place visited. However, one may also need image categories, such as "nature", "urban", "people" and so on. Should then Fido.jpg be under 2021-05 London or under Animals Dogs?

In practice, the "photo archive"-type dilemma is often resolved with a system of tags, which effectively allows placing an element into any number of independent hierarchies. I can have tags like Dog under the category of Animals and London under Places, and assign both tags to a specific photo. Then I can browse my photos using any of the hierarchies I have according to my current needs.

Just to be clear, I am trying to make a simple point here. The organization of a system as a hierarchy is not something "natural". It is a deliberate engineering decision that takes effort to implement. The benefits are clear: such systems possess numerous attractive features like simplicity, maintainability, reusability of components, etc. The costs, however, should also not be overlooked: it takes effort to make independent units compatible, and to shoehorn your problem domain into a concept of hierarchy, which might be not easy at all. One simple example of the cost of compatibility is seen in any electronic component, such as a transistor, which is 99.9% "interface" and only the rest is "implementation":

The interface here is literally everything except the tiny block in the middle, and its only purpose is to enable us to hold the transistor in hands, mount it on a board and connect with other components. By eliminating this interface, we can save a lot of space and building materials, which is exactly the logic behind integrated circuits. An integrated circuit, however, is a complete circuit, so we have to design our system in a certain way to make it fit. It is also probable that some of the circuit’s components and capabilities won’t be necessary for us, turning them into a wasted resource.

The Growth of a System

As the number of components in the system grows, the number of possible connections between them grows quadratically. A "connection" is also a kind of entity that takes space in our mental map, so we are interested in reducing both the number of components, and the number of intercomponent connections. Thus, any extension of system’s functionality imposes architectural challenges. How to proceed?

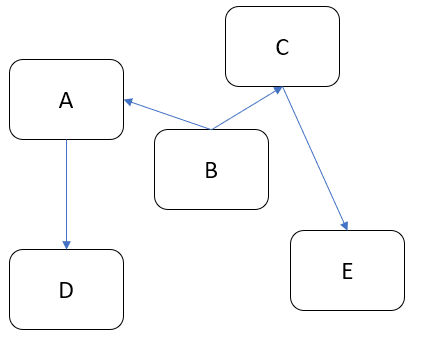

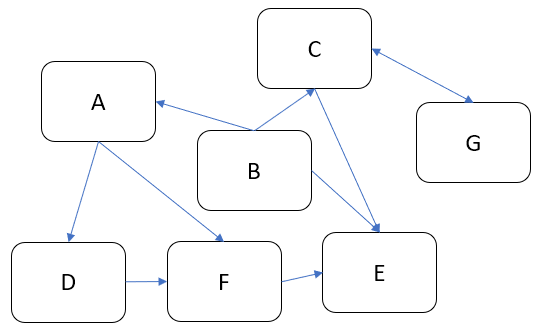

Let’s say I have a system made up of several connected components:

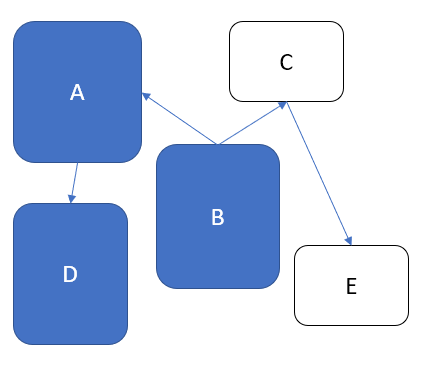

Link directions show how communications flow. For example, B needs to talk to A and C, but A and C don’t have to talk back. Suppose I need some extra functionality. How can I add it into this scheme? Basically, there are two principal choices. I can spread functionality across existing components, thus making some of them bigger:

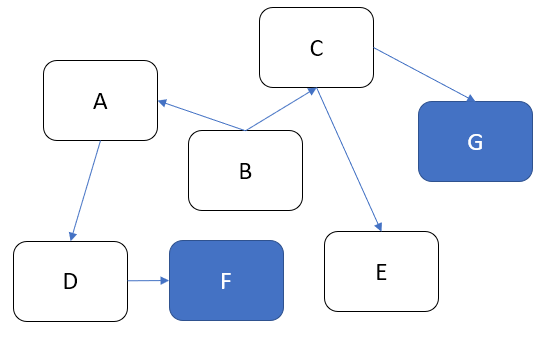

Alternatively, I can introduce additional components:

The first method (make the components bigger) is usually frowned upon, but it actually makes sense if used carefully. It’s easy to call this approach "lazy", but it fights complexity by preserving the overall count of components and connections (at the expense of making individual components more complicated). The second approach can be seen as an opposite strategy: we keep the components small, but their count goes up, increasing the complexity of our system.

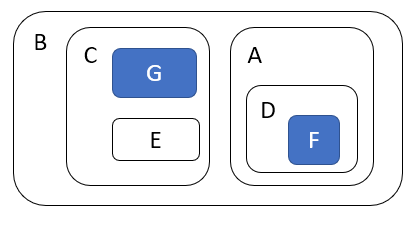

If both methods are aimed to achieve the same goal, why most sources vocally support the latter option? That’s because large components are hard to simplify (so it’s a dead end eventually), while the network of small components can be transformed into a hierarchical Matryoshka-like structure:

What is interesting here is that the transformed system works exactly the same as its network-like version. We use the same objects, and they communicate with each other in the same way. The only change is visibility. Most objects are hidden: I won’t see D until I have to figure out how A works. The cognitive load can be reduced tremendously.

However, as anyone in the field can attest, we don’t really live in the world of "tremendously reduced cognitive load". It doesn’t look like a typical codebase we have to work with is constructed in a Matryoshka-like manner. There are a few reasons for this phenomenon. For example, we can observe that some systems are not hierarchically organized and thus cannot be easily transformed into a Matryoshka architecture:

Probably, this last picture is very not realistic anymore, but not impossible either. Even bidirectional or circular links do occur sometimes, so we shouldn’t ignore their existence.

I also have to say that even a perfectly hierarchical system isn’t without downsides. It is fine when it works correctly. When things go awry, debugging such a construction can be a pain: we peel a layer after layer off this onion and still cannot reach the the place where something is actually being done. There are usually many interfaces, adapters and other "glue" blocks that simply pass data here and there. Unit tests should help to some extent, but they aren’t 100% bullet-proof either. This architecture is also quite rigid: rewiring objects living "on the surface" is easy. However, if I realize that I really need to talk to an object located in another object’s private zone, things might get tricky.

So it seems to me that the right goal to pursue is to keep the balance. A function of 200+ lines of code is perhaps overly long, but I wouldn’t refactor a function of 30 lines on the basis of length alone. Similarly, if I see that the object is dealing with 3-4 other objects, it feels acceptable, just don’t let this list grow too much.

Transparent and Opaque Hierarchies

So far, I’ve been mostly reiterating the issues most of us understand very well. Now I am coming to something different that bugs me. Let’s consider a fragment like this:

class X:

pass

class Y:

def __init__(self):

self._UnitX = X()Is this "a network of small connected elements" or a "hierarchical Matryoshka architecture"? It seems that most sources don’t discuss this distinction much. An instance of A has a private member of type B, so in this sense the B-component belongs to the A-component, and, therefore, it is "inside" A. It is also clear that nobody can access the B-component from the outside (or "not supposed to access" in case of Python).

If someone asks me to represent the case of Figure 4 in code, I’d do something like this:

class A:

def __init__(self, d):

self._UnitD = d

class B:

def __init__(self, a, c):

self._UnitA = a

self._UnitC = c

class C:

def __init__(self, e, g):

self._UnitE = e

self._UnitG = g

class D:

def __init__(self, f):

self._UnitF = f

class E:

pass

class F:

pass

class G:

pass

g = G()

e = E()

c = C(e, g)

f = F()

d = D(f)

a = A(d)

b = B(a, c)Here we have independent global objects hooked up together so they can communicate. To transform this code into the system shown in Figure 5 we need to get rid of global objects:

class A:

def __init__(self):

self._UnitD = D()

class B:

def __init__(self):

self._UnitA = A()

self._UnitC = C()

class C:

def __init__(self):

self._UnitE = E()

self._UnitG = G()

class D:

def __init__(self):

self._UnitF = F()

class E:

pass

class F:

pass

class G:

pass

b = B()I think many authors stop at this point, declaring the system sufficiently decomposed. This isn’t wrong, but still leaves me dissatisfied. Yes, objects here are stored inside other objects, so the system in its current form is fine. However, systems develop over time, and "its current form" can be modified at any moment. When I see that a certain member is declared private, I treat it as a deliberate design decision, and reluctant to make it public (or pseudo-public with a getter) without serious reasons. However, all types are public here, so I have no idea whether a certain type, such as F or E, is designed for general use or not. Thus, I don’t really feel motivated or demotivated to use F or E in my own extensions of the system. The types are there, and that’s all I can say about them.

Let’s compare it with real-world systems. I said that a coffee machine contains a grinder inside, and the grinder contains an electric motor and steel blades. However, if I disassemble the machine, I won’t see them unless I also disassemble the grinder. I wouldn’t even know that there are things like blades or motors inside the system at all. Not only objects, but also types do not contaminate my mental map of reality. So, a hierarchy of a coffee machine is less transparent than of a typical software system, and imposes lower cognitive load.

An Issue or a Non-Issue?

Now I need to restate the basic point of this article. Overly large classes or units and overly complex functions are very common in code I have to deal with. I am sure I am not alone in my misery. Reorganizing code into small units and simple functions is a separate effort, requiring motivation, time, commitment and skills. If some of these factors are missing, we’ll have an overly complex system or even a Big Ball of Mud. Tools like Black or Lizard help to keep an eye on complexity indicators, so I’d say that the "early warning" system is easy to setup. However, very often a codebase after refactoring doesn’t really look significantly simpler. Instead of a small collection of large objects we get a large collection of small objects. My goal is to understand why it happens, and what can be done about it.

However, at this point the situation looks much less clear to me, and I am not so confident in my reasoning anymore. To begin with, the statement above is based on my personal experience, which is very biased. Every time I open a project and see a large collection of files, no matter how carefully organized into folders, I have a distinct feeling that eventually I’ll have to go through most of them to figure out what’s there, and how those pieces work. Maybe it’s worse than "in average".

Next, maybe I am exaggerating the issues arising due to "type space contamination". It’s hard to measure them, but I have one idea that will be hopefully elaborated later: what if in addition to a conventional "contamination" argument we consider something like "robustness score"? Suppose I have a system made of classes with all-public functions. I understand that some of them are logically private, and name them using lowerCamelCase(), while "true public" functions are named in UpperCamelCase(). Nobody prevents me from calling a "private" function, so I can do something undesirable directly without any modification of the system. Thus, the "robustness score" is zero: there is no armor to break. Now, suppose I actually declare a certain function private. In this case, to do something undesirable I need two steps: make it public again, then call it. It means the "robustness score" of one.

Similarly, suppose I have a class that was extracted from another class during refactoring. It is coupled with the first class, and not really designed to be used elsewhere, which means using it is plain dangerous. Since we are not doing it, the system is safe, but its "robustness score" is one: I can first create an instance of the extracted class, and then use it (which is undesirable). Thus, hiding such internal types makes the system more robust; it is harder to break it without a certain deliberate effort.

One might ask, but aren’t we as careful about visibility of classes and types as about visibility of variables and functions? I am afraid that no. It seems that the separation of class members into public and private is well internalized, so even little code snippets in books and online blogs don’t try to cut corners by omitting access modifiers. (This is less often the case for languages like Python, where non-public access is more a matter of convention than a part of the language). For comparison, let’s see, for example, how a typical text on "extract class" refactoring technique deals with the appearance of extra classes in the system as a result of proposed modifications.

Here is a case study from Martin Fowler’s site (it’s not his article, but apparently endorsed by him), here is an example from ReSharper documentation, and here is a blog post discussing refactoring large classes. None of these articles 1) try to change the visibility of newly extracted classes (so they have the same level of visibility as the original class); 2) mention this issue at all.

I don’t really know whether I’ve just hit on unrepresentative examples, or most authors do not consider the topic important, or there are some other factors at play. I’d say that the tools for class-level visibility enforcement are quite different across languages, so people might consider distracting to talk about them.

The Toolset

Probably, the closest mechanism for the opacity I am talking about would be an option to declare classes and types to be visible only to certain other classes. The concept of nested classes in Java/C++/C# comes close, but a nested class have access to private members of its outer class, which makes it more like a convenient way to group certain class members. In Java, the members of an outer class are even considered to be the members of its inner classes as well, which blurs encapsulation even further.

The next best thing would be to declare a class to be "package-private". This option exists in Java, but does not in C# or C++. (I am not talking about Python, because everything is "public" in Python, and the usual naming conventions do not differentiate between possible levels of privacy). In general, modules/packages in most mainstream languages are primarily considered as means of creating structure rather than enforcing access rights. We see this decision at play on a daily basis:

# Python

import os.path

// Java

import java.net.Socket;

// C#

using System.Collections.Generic;There is nothing unusual in using a nested package name such as net inside java. Thus, there is no perception that we are entering a private zone. This is the main reason for my feelings expressed before: no matter how carefully the folders / packages / whatever are organized in a system, it’s still hard to tell whether the classes declared in the coffeemaker/grinder/motor directory are designed for the use outside or not. Naturally, we can always come up with certain conventions and rules. For example, in Java I can suggest to make all non-API classes package-private (this is the Java default option anyway), and to communicate only with the classes in your immediate surroundings, i.e., declared in the outer package of the current package and in subpackages of the current package. There might be valid reasons for accessing faraway objects, but they should be treated like singletons: use sparingly and with care. However, as a user I have no idea whether such conventions are respected in the codebase I am dealing with, so not checking the code inside subdirectories is still not an option.

Closing Thoughts

I understand this post might look like a bunch of loosely-connected notes, peppered with rants about the sorry state of object visibility enforcement rules in mainstream languages. What’s constructive here? Well, I admit I am still thinking how to approach this issue in the right way. What I know is:

refactoring a system of large classes into smaller classes produces too many visible object types messing around;

typical texts on refactoring mostly focus on lower-level issues (but I admit I should go through my reading list);

language designers for whatever reasons are concerned mostly about class-level access control mechanisms, allowing to specify how class members interact with the objects of other classes (related via inheritance, aggregation, or completely unrelated).

I can only speculate that most languages around are quite complicated already, and there is little incentive to introduce new sources of complexity. On some level naming conventions work reasonably well: modules / packages / directories named like detail or impl, are widely used, signaling their "internal" nature to the reader. Maybe I am missing some obvious tools, but now it seems that developing a matryoshka architecture consisting of sufficiently opaque objects is more challenging than one might have expected.